100th HARPIA Spectroscopy System—and Counting

Light Conversion celebrates another achievement this November as the company ships its 100th HARPIA ultrafast spectroscopy system. The system performs a variety of sophisticated time-resolved spectroscopic measurements, allowing to explore processes in various materials with femtosecond temporal resolution. Ultrafast spectroscopy, for example, provides insight into how plants, algae and bacteria employ light to synthesize sugar from carbon dioxide and water, or what occurs inside the retina when it is hit by a photon. After all, these processes occur in less than a picosecond—how else could we study them if not with femtosecond lasers?

The roots of Ultrafast Spectroscopy

Although the HARPIA product line debuted in 2012, the field‘s history dates back much further. As early as 1940, even before lasers existed, researchers began examining photochemical reactions on the microsecond time scale. Molecules in various solutions were excited – or even split – by brief flashes from xenon discharge lamps, resulting in changes in the absorption spectrum of the solution. After a cuvette containing the solution was exposed to lamp light, its spectrum was recorded by photomultipliers and and the resulting spectral changes from the flash were displayed on an oscilloscope. These were the first observations of short-lived radical reactions, discoveries that later earned R.G.W. Norrish and G. Porter the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1967. Consequently, the method was termed „Flash Photolysis“ and remains widely used today in scientific research for nanosecond and microsecond absorption experiments.

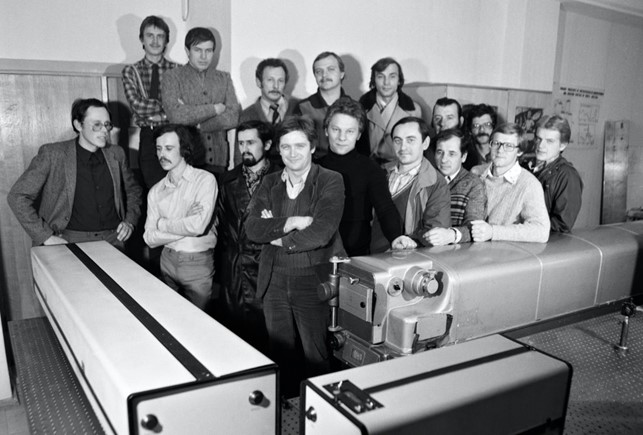

With the advent of lasers, scientists quickly learned to shorten the light flashes to nanosecond, picosecond and eventually femtosecond durations. It became evident that nature is full of light-induced processes that operate on these incredibly short timescales: photosynthesis in plants, charge relaxation in crystalline and amorphous materials, and molecular vibrations all occur in mere femtoseconds. The development of picosecond lasers and semiconductor light-detection devices propelled the study of these rapid phenomena to new heights. A group of scientists from Vilnius University, including the future founders of Light Conversion, created their first picosecond spectrometer in 1979, while A. Zewail won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for femtosecond spectroscopy research in 1999. However, back then, most scientists had to design and build their own equipment, as femtosecond lasers were still a novel and rare resource.

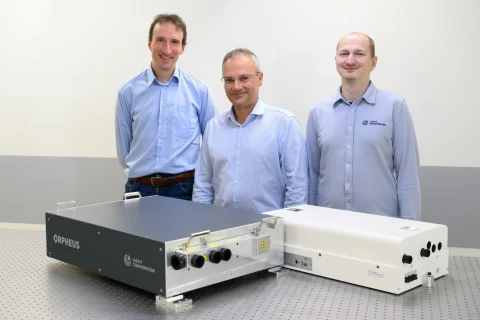

The initiative to advance ultrafast spectroscopy systems was spearheaded by M. Barkauskas and M. Vengris, who currently hold positions as Light Conversion‘s CEO and a professor at Vilnius University’s Laser Research Center, respectively. In 2006, they successfully built their first spectroscopy system—the prototype for HARPIA—on an optical table. While this early model works just as effectively as modern devices to this day, it had nearly 10 times the footprint. Finally, following the development of the Yb-based PHAROS femtosecond laser and ORPHEUS optical parametric amplifier, the first HARPIA spectrometer was introduced in 2012. This year marked its debut at the Photonics West industry exhibition in San Francisco and the acquisition of initial clients, including Kyoto University in Japan and the National Research and Development Institute for Isotopic and Molecular Technologies in Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

HARPIA today

HARPIA spectroscopy systems have allowed clients to access all essential equipment from a single supplier: ultrafast lasers, optical parametric amplifiers, spectrometers, as well as measurement and analysis software. Today, the system offers three extension modules built around the HARPIA-TA transient absorption spectrometer to customize the system to specific measurement needs. It can be expanded with modules for time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC), Kerr gating and fluorescence upconversion (HARPIA-TF), third-beam delivery for multi-pulse experiments (HARPIA-TB), and microscopy (HARPIA-MM).

Additionally, Light Conversion’s team, led by K. Redeckas, launched the HARPIA-TG in 2022 – a novel transient grating spectroscopy system designed to measure the diffusion coefficient, carrier lifetime, and diffusion length through direct optical means. This fully automated, computer-controlled system enables measurements in a matter of minutes, making this complex technique accessible to a wider audience. HARPIA-TG allows the characterization of electrically nonconductive or non-fluorescent samples, making it suitable for semiconductor materials and derivatives, e.g., silicon carbide (SiC), gallium nitride (GaN), perovskites, organic and inorganic solar cells, quantum dots, and even complex nanostructures such as quantum wells. This unique spectrometer earned the Golden Honoree nomination at the 2022 Laser Focus World Innovators Awards.

And there’s more to come.

The world of Ultrafast Spectroscopy

Molecular vibrations, electronic transitions, chemical reactions, energy transfer, and fluorescence are all examples of processes that spectroscopy can investigate. It allows researchers to uncover the dynamic properties of molecules and materials across a broad range of time scales, aiding our understanding of fundamental processes in chemistry and physics, as well as material characterization for solar cells or light-emitting diodes. However, among the most exciting applications for ultrafast spectroscopy systems is the study of photosynthesis.

Photosynthesis begins when light photons are absorbed by the light-harvesting complexes – arrays of proteins and pigments that capture light and channel its energy to the reaction center. These complexes contain essential light-absorbing pigments, carotenoids and chlorophylls: carotenoids capture blue and green light, while chlorophylls absorb blue and red light. This absorption happens in mere femtoseconds, after which the pigments enter an excited state. Within the complexes, pigments are arranged in close proximity to ensure efficient energy transfer, allowing light to reach the reaction center within just 10-100 picoseconds, where further electrochemical reactions unfold.

By employing femtosecond spectroscopy, scientists can observe these stages of light absorption, energy transfer and pigment states in great detail. This provides a “map” of how the absorption and fluorescence of each pigment change over incredibly short time frames, helping to understand the complex chemical steps from light absorption to final energy conversion into energy-rich organic carbohydrates and oxygen. Research into photosynthesis using ultrafast spectroscopy not only delves into the fundamentals of life, but also stimulates the development of new technologies, such as artificial photosynthesis, paving the way for sustainable energy solutions.